|

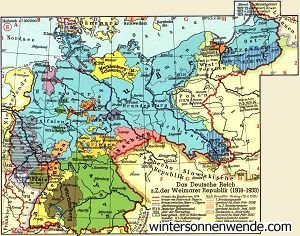

The Beleaguered City In order to understand Hitler's denunciation of the Treaty of Versailles, it is necessary to realise the strategic position of Germany at the time he came into power, and to compare the map of Europe at that time with the map before the war. Germany is bounded by other countries, except along the Baltic, and if we proceed to trace this post-war frontier we shall find that the title given to this chapter was fully justified at that time. We shall begin with the frontier facing France. Alsace and Lorraine, which had belonged to Germany since the war of 1870, were restored to France. These territories which contain a mixed French and German population, have changed hands more than once. Louis XIV seized them in time of peace, and they continued to be part of France after the close of the Napoleonic wars, to be regained by Germany in 1870. France never ceased to look forward to their recovery; the statues in Paris representing the two provinces being always draped in black. It is probable that if they had not been taken by Germany in 1870, the war of 1914 would have been confined to Eastern Europe. While the Treaty of Versailles was being drafted, Foch wished to have the whole of the Rhine

The Treaty of Versailles re-created the country of Poland out of Russian, German and Austrian territory, and in order to give Poland an outlet to the sea, presented her with a broad strip of land on the Vistula, ending in the town of Danzig, which was made a free city under the suzerainty of Poland and the League. This strip of territory cuts off East Prussia from the rest of Germany. Difficulties have arisen over Danzig, the population of which is more than 90% German, difficulties which have been increased by Poland building the new port of Gdynia in the neighbourhood, on Polish territory, to which her sea-going trade is being diverted. The Polish corridor contains a mixed population of Poles and Germans, and was given to Poland without a plebiscite. According to the German census of 1910, it contained a majority of Germans. A considerable section of Silesia, including three quarters of the valuable Silesian coal fields, was given to Poland in spite of a plebiscite in favour of retention by Germany. As this extensive minefield had been developed by German capital, and contained a considerable German population, this region has also been the source of endless difficulties. One of the causes of trouble is the low standard of living and wages of the Polish miner, wages which the German miner who was handed over has had to accept. The Treaty of Versailles carved up the whole Austrian Empire, creating the new country of Czecho-Slovakia, which contained six different races over whom the Czechs, having a small majority, have ruled. Bohemia which, as can be seen from the map, cuts into the heart of Germany, was formerly part of the friendly Austrian Empire, but now belongs to Czecho-Slovakia. It has been a bone of contention between the Czechs and the Germans for centuries, contains a population one third German and two thirds Czech, and includes the important historical city of Prague. The German population suffered severely under Czech rule; the Czechs never having carried out the clauses in the Peace treaties designed for the protection of minorities. Czecho-Slovakia is a democracy, but a democratic government is no protection to an alien race in a permanent minority, and the Czechs kept their prisons full of German political prisoners. It is generally admitted today that the commissioners who drew up the new frontiers showed very little wisdom or knowledge of the various peoples whose fate they were deciding in an arbitrary manner. They refused a plebiscite which had been promised by Wilson whenever it suited their purpose.

No one therefore who looks at the map can doubt the correctness of the title I have given to this chapter. The huge guns of the Maginot line can destroy the German towns to 20 miles behind the frontier, and it forms a military base for the invasion of the Rhine provinces; while a Russian fleet of bombing planes planted in Bohemia can destroy the cities of Germany. The invasion of the Ruhr by France in time of peace had shown Germany what to expect from her neighbours if she remained in this vulnerable position to the enemy without the gates. In addition, at the time when Hitler came into power, the Communist vote had risen to 7 million, and the German people had already experienced the horrors of a Communist rising in Munich, Central Germany, the Ruhr Valley and in Hamburg. Horrors that would have been repeated all over Germany if Hitler had not acted promptly. Germany's very existence depended on a highly centralised government; a stern internal discipline; the training to arms of the young men; the possession of munitions not inferior to her neighbours; and the organisation of the whole nation for one purpose, the preservation of the German people from attack. Germany is not in the position to attack, nor desirous of attacking any nation in Europe; but no nation could be expected to tolerate for long this policy of encirclement without taking measures for defence.

|