|

German Rule and Mandate Rule Compared Hitherto attention has been concentrated upon the more negative aspects of the question at issue, since it was necessary to rebut baseless charges, adjust false perspectives, put questions in a right and true light, and correct misrepresentations generally - misrepresentations due sometimes, no doubt, to pure though culpable ignorance, but more often, it is to be feared, to malice and a wish to deceive. To say all that would be possible and justifiable on the positive side of the question would entail the writing of a whole series of books on German administration and what it has done for territories redeemed from conditions of disorder, violence and savagery. Here no more than the merest outline of the full story can be given.

After all, the best answer to the accusations made against the Germans in the Covering Note of the Treaty of Versailles is to point to their more outstanding achievements in the development and civilization of the colonies before the war - achievements which were often of the greatest importance for the colonies of all nations. Names like those of Nachtigal, Schweinfurth, Wissmann, Emin Pasha, Stuhlmann, Baumann, Hans Meyer, Kandt, Count Goetzen, and Duke Adolf Friedrich of Mecklenburg are known and respected in expert colonial circles everywhere. It would be easy, however, to make the list twice as long, in order to show how great a share has been taken by German explorers and savants in the scientific exploration of the Dark Continent. In all branches of science and knowledge - in ethnology, philology, botany, zoology, etc. - are encountered the names and the discoveries of German scholars, missionaries, and travellers. No one has paid a more generous tribute to the achievements of the German colonial explorers, discoverers, pioneers, and scientists than the distinguished English authority Sir Harry Johnston in his books on Africa. I mention only his Opening up of Africa, pub- [145] lished in 1911 (see pp. 238-41). A recent very characteristic example of the real understanding and love for the peoples entrusted to his care which filled the soul of many a German official is the collection of Samoan proverbs published by the last Governor of Samoa, Dr. Erich Schultz, in the Süddeutsche Monatshefte for March, 1914. But the greatest claim to fame which can be made by colonial Germans lies in the realm of medicine and hygiene, and particularly in the fight against the tropical diseases and plagues that beset white men, black men, and beasts alike, in the regions in which they have spent health, strength, and often life itself. Nearly thirty years ago the British Foreign Office began to recognize and praise the scientific work done in the German colonies at the instigation of a Government and nation now declared to be unfit to colonize. Thus a report of that Office on East Africa (C 8649-3) for 1897 stated:

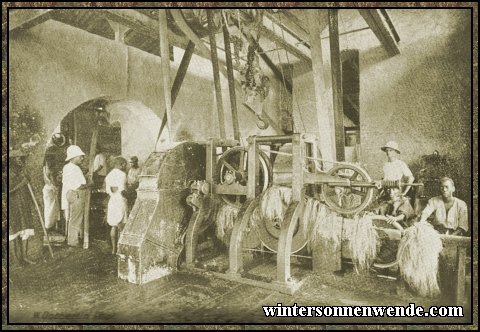

"Progress has been made in scientific work, both in the way of exploration and medical, botanical, and geological research. It may be confidently hoped that the results of the inquiries now zealously conducted in the German colonial establishments will be to add to the world's knowledge as to the hygienic conditions of life in tropical climates and the method of cultivation of tropical plants." Many such tributes were paid in later years both in British official reports and in those of scientific investigators and travellers. It was the great German scientist Robert Koch who, in the course of repeated sojourns in British and German colonies, made such epoch-making discoveries and laid the foundations for the extirpation of various scourges. The blessings which this man and other German scientists and doctors after him have conferred on the tropical colonies - and by no means only German colonies - by their successful methods of combating disease are beyond calculation. I need only remind the reader of the discovery of the Cholera Bacillus and of the resulting battle against Cholera in India and of the organization undertaken for the fight against the Sleeping Sickness, the Rinderpest and other plagues in Africa. Many [146] scourges which formerly afflicted the native population and exacted a terrible death-rate - for example, Smallpox, have almost lost their significance in the German colonies, thanks to the unremitting labour of German science, both theoretical and practical. Other diseases, against which the natives were formerly entirely helpless, such as Framboesia and Syphilis, have been successfully cured since the discovery of Salvarsan. It is a satire upon justice and a reproach to civilization that at the present time German scientists are obliged to engage in investigating pathological problems, of vital interest to the human race, in territories under alien rule on sufferance owing to the closure of our own Protectorates to them. For despite the seizure of the German colonies, the German zest for discovering new methods to combat disease continues unabated. In Germanine (Bayer 205) Germany has now discovered a certain remedy against the deadly Sleeping Sickness. At the moment of writing, a German expedition under the leadership of Professor Dr. Kleine, which had been two years in the British and Belgian colonies in Central Africa in order to test the efficacy of this remedy, has just returned home. Professor Kleine has established with certainty, by means of a great number of cases, that this remedy is capable of quickly and permanently curing this terrible scourge. This not only means salvation for the unfortunate mortals cursed with the Sleeping Sickness, who have hitherto been doomed to long suffering and generally to death, but it also signifies the restoration to life and economic activity of great districts in which the native population was dying out. The effects of this remedy have also been very favourable in the case of combating the bacillus of the illness induced by the tsetse fly. Whilst not as yet so auspicious as in the case of the Sleeping Sickness, there are many indications to prove that this German remedy will also succeed in ridding Africa of this second scourge - a prospect which opens up enormous vistas for the social and economic improvement of a great part of the Dark Continent. I may also mention Dr. Albert Schweitzer, who has already done so important and noble a work of research in Central Africa in connexion [147] with the cure of Leprosy as well as Sleeping Sickness, as many distinguished Englishmen well know. It is a matter beyond dispute that the scientists of no other civilized country have done so much by means of discoveries and the organized fighting of diseases and plagues as those of Germany. In view of facts such as these, what name should be given to that spirit of defamation, so unworthy and so unmanly, which still persists in declaring that the Germans have been failures in the field of colonial civilization? It is a singular tribute to German scientific eminence and worth in the domain of tropical hygiene and medicine that there were English writers who called upon their Government to require from Germany, as one of the penalties of defeat in war, that she should communicate to other countries the pathological discoveries made by her great investigators and practitioners. The enormous development of the German colonies during the short period of thirty years which elapsed between their acquisition and the outbreak of the war had impressed and astonished every traveller and scientist who had the opportunity of visiting them. Where there was formerly nothing but wilderness, interrupted merely by thinly populated native settlements, flourishing plantations had arisen producing, under European supervision, important values for the markets of the world.

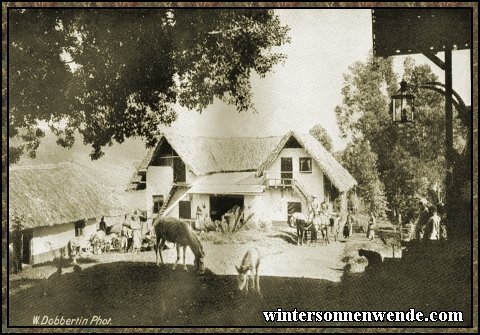

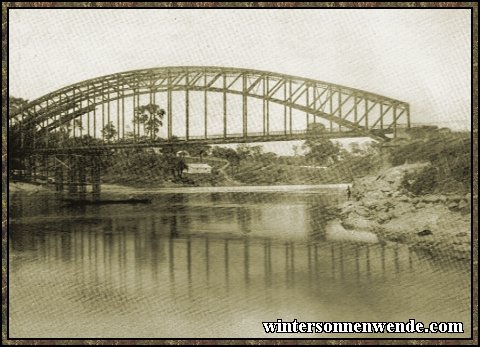

Vast regions of bush, formerly devoid of all human life, had given place to farms, with their ever-increasing herds of cattle. Where a few precious products had aforetime been carried to the coasts by caravan for weeks and months on the heads of carriers, where dense jungles made advance almost impossible, where sand-dunes and deserts with their burning wastes scarcely permitted traffic even by ox-team, spick-and-span modern railways offered quick and safe communication between distant points, opening up great hinterlands, and enabling the tribes of the interior to emerge from their seclusion and participate in the great tasks of economic development.

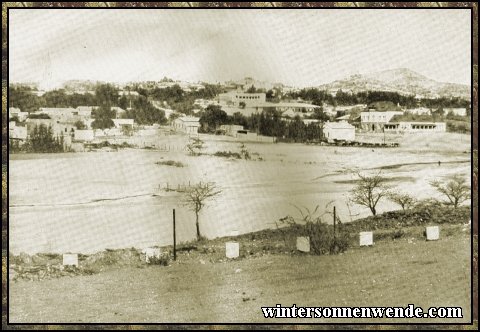

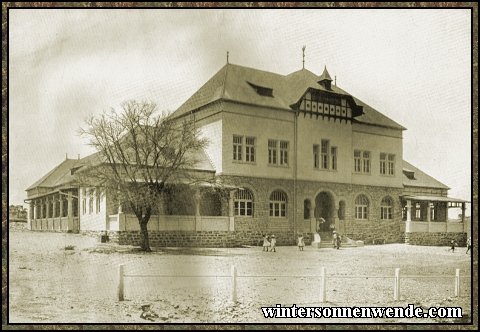

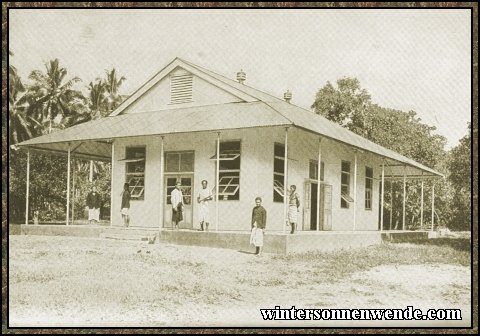

Coast settlements which at the most were tiny villages when the German flag was hoisted had grown into modern towns, which were taking an ever-increasing part [148] in world commerce. Wherever the traveller turned, whether to Tsing-tao in China, to Dar-es-Salam in German East Africa, or to any of the other neat and orderly seaports in the German colonies, there he was sure to find fine, well-planned and well-built towns which more than held their own with similar towns in alien colonies. The same may be said of the German railways and arrangements for traffic, of the plantations, and of the entire German colonial administration.

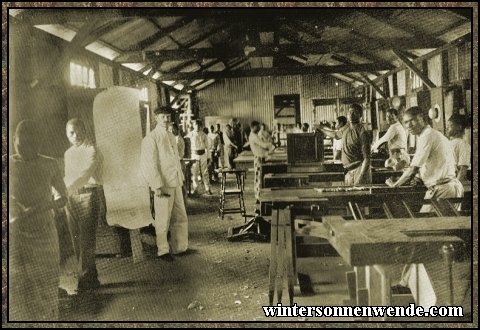

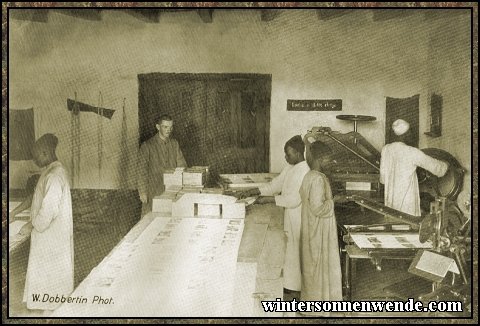

German solicitude for the health of the natives did not confine itself to the warfare against the diseases that afflicted man and beast, as above mentioned. Every care was also taken for the individual treatment of sick natives. Doctors, specially trained at home in the treatment of tropical diseases, devoted themselves to the care of the native communities, and their numbers grew from year to year. A considerable number of native hospitals were already in existence for the care of those suffering from serious maladies, and others were constantly being added. Minor cases were treated free in the polyclinics, and the natives made much use of these benefits. In all German colonies large sums of money were set apart for the medical needs of the natives, and provision was made for the free use of the expensive new remedies for tropical diseases. British military and other officers who have made acquaintance with the German colonies since 1914 have referred in terms of amazement and admiration to the remarkable work of their predecessors in town building, and have recommended German achievements in this sphere for imitation by their countrymen. No less warmly have British medical practitioners spoken of the wonderful hospitals and the hygienic service established by Germany in her oversea territories.1 A great work has been accomplished in the training of the natives to regular labour, while schools for artisans have disseminated useful technical knowledge and afforded them the opportunity of learning and following crafts and trades. It is a high compliment to German efficiency that when the British occupied German East Africa they found it expedient [149] to transplant native artisans, trained under German auspices, into the adjacent British colony, to instruct the more backward natives there.

Agricultural schools have likewise extended the knowledge of modern and progressive forming methods, and enabled the natives to cultivate many new and profitable crops. The schools for the scientific study of cotton and other tropical plants which had been established in some of the colonies were also proving of great use and value to the natives.

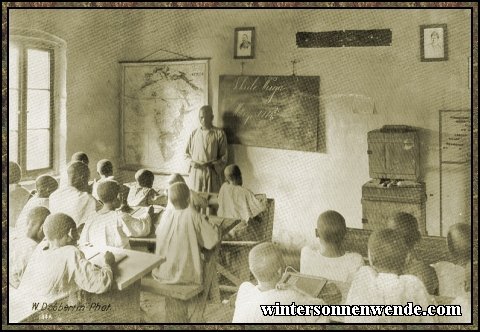

In all the colonies, too, great concern was shown for the spiritual welfare of the natives. Numerous missionaries of the two great branches of the Christian religion were occupied in evangelizing the native population, which for the greater part was found sunk in the darkest heathenism. Many schools, Government as well as mission schools, were devoted to the education of the natives. Yet even our self-sacrificing missionaries have not been spared abuse. They are said to be guilty of political propagandism. But how and where? If they represented German national interests in German colonies, they were in the right. To say that they sought to prejudice the natives against their masters in British territories is to make a charge that cannot be substantiated. In fairness to these devoted men I must cite in their favour two recent unbiassed testimonies, one from an English and the other from an American source. Dr. Frank Lenwood, one of the leading officials of the London Missionary Society, in a letter to The Challenge of May 10, 1918, stated:

"I am driven to the conclusion that the charges against them are due to suspicions, natural enough in war-time, but without real foundation, and that the statement has been repeated so often upon scanty evidence that it has come to be accepted as a fact. The great and unselfish service of German missions under the British flag calls for an impartial scrutiny of any statement made against them." The Rev. Cornelius H. Patton, D.D., Corresponding Secretary of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, stated at the Africa Conference held in New York City in November, 1917:

[150] "Africa cannot afford to lose the help of the German societies which were established in various parts of the continent before the war. The German missions in Togoland, in the north part of Cameroon, in German South-West Africa, and in German East Africa were being blessed of God in signal ways. They were making a unique contribution to Africa's evangelization and civilization. Their missionaries were second to none in self-sacrifice and zeal. Whatever geographical and governmental changes may occur, it will be nothing less than a calamity to the Kingdom of God if the Christian people of Germany are to have no further part in Africa's redemption."

The perils which European civilization entails for the primitive races in many ways were forestalled in the German colonies by a number of wholesome regulations. Trading in firearms was forbidden to natives and was in general subjected to a rigorous supervision. The sale of alcohol to natives was entirely prohibited in certain colonies, such as German East Africa and the South Sea Islands, while in the other colonies measures had been taken in accordance with international agreements to reduce to a minimum the danger arising from the use of alcohol. The natives were also protected against exploitation by Europeans through the provision that all contracts between whites and natives were subject to official approval, and that any attempt at evasion rendered the contract invalid. Land commissions or other authorities took care that wherever a sale of land by natives to whites took place sufficient acreage was left to the natives resident in the neighbourhood, and for their progeny. The impartial justice meted by the German officials gave the natives efficient protection from wrong and damage whether from whites or from fellow-blacks. The object constantly kept in view was the conservation of the health and bodily welfare of the labourers and their protection against exploitation. It has been clearly shown that the seizure and partition of the German colonies were in no way justified by the slanders which were invented and disseminated for the simple purpose of giving to these acts the force of a specious moral sanction. This fact became evident soon after the booty in the shape [151] of Mandates had been divided out, and it became clear that the mandatories were proving incapable of maintaining these colonies at the high level set by the Germans.

Thus Mr. Winston Churchill, when British Secretary for the Colonies, stated before the Imperial Conference on June 21, 1921, in relation to German East Africa (Tanganyika):

"We have endeavoured to equip it with a government not inferior to the German administration which it had replaced... I am afraid that in a year or two the state of this Tanganyika Territory will compare unfavourably with its progress and prosperity when it was in the hands of our late opponents."2 This prophecy has been fulfilled in a startling manner, for conditions in German East Africa became most doleful, as will be shown in later pages. Further, Mr. Ormsby Gore, the British Under-Secretary for the Colonies, stated in the House of Commons on July 25, 1923, apropos of the same German colony:

"The mere fact that propaganda is still going on in Germany makes it absolutely incumbent upon us to give that vast territory, which in area is larger than Nigeria, and contains a population just over 4,000,000, at least as good and complete an administration as was given by the Germans in that country before the war."3 The British report upon the Cameroons for 1921 speaks thus of the German plantations there:

"As a whole they are wonderful examples of industry, based on solid scientific knowledge."4 The same report goes on to say:

"Apart from the regular employment afforded, the natives have been taught discipline and have come to realize what can be achieved by industry. Every labourer is an embryo planter. Large numbers who return to their villages take up cocoa or other cultivation on their own account, thus increasing the general prosperity of the country."5 [152] Finally, as to German South-West Africa General Smuts, whom everyone will allow to possess exceptional experience in colonial matters, referred to the Germans, in a speech made in that Protectorate on September 16, 1920, as splendid colonists who fully deserved the Government's support and encouragement.6 Later he wrote to Privy Councillor Herr de Haas, a high functionary of the German Foreign Office, who was then in London:

"The Germans settled at various times in various parts of the Union form one of the most valuable portions of our South African people. And I feel sure that the Germans of South-West Africa, whose successful and conscientious work in the territory I highly appreciate, will materially help in building up an enduring European civilization on the African Continent, which is the main task of the Union" (letter of October 23, 1923). It is a simple act of justice to say that it was only in the Union of South Africa that a humane policy, and one in accordance with international law, was followed in the treatment of German subjects after the war. The Government of that Dominion refrained from beggaring the Germans of the South-West by expropriating their property without compensation, and even the concessions to which titles could be established were respected. It redounds to the honour of British and Dutch South Africans that when General Smuts announced to the Cape Town House of Assembly the decision so to act his words were "received with repeated cheers from all sections of the House."7 Considering the peculiar psychology of the French, it is difficult to conceive of their giving credit to German achievements of any kind. Nevertheless, even the French official Mandate reports cannot entirely suppress a certain recognition of what the Germans accomplished in the field of sanitation. The first of these reports states:

"It is absolutely indisputable that the Germans in the Cameroons had begun a great under- [153] taking in the matter of medical assistance, and that this had begun to bear its benevolent fruits."8 A later report (1921) concedes that "no inconsiderable results had been attained in this direction."9 Further, a French newspaper wrote as follows in August, 1923, regarding the colonial activity of Germany in West Africa:

"If all French colonies were equipped like the Cameroons and Togoland, a great step forward in their profitable development would be achieved. France, in all circumstances, must not fail to improve that which the Germans had already realized in their colonial territories as early as 1913."10

The first achievement of the Mandatory Powers which accepted the office of administering the former German colonies on behalf of the League of Nations was that they laid down arbitrary frontiers in various colonies, so dividing tribes which were naturally homogeneous. As has been made plain in earlier chapters of this book, the partition of the colonies was not undertaken in any degree whatever from the point of view of the welfare of the natives concerned. On the contrary, the only consideration was to possess them and to do it with as little show of scheming, selfishness, and cupidity as possible. It has also been shown that in some cases the division was simply a realization of earlier agreements concluded secretly and never divulged to the world. The consequence is that in the West African colonies of the Cameroons and Togoland, which were divided between France and Great Britain, the tribes have been violently torn apart. In Togoland this has happened to the tribes of the Ewe, the Konkomba, and the Tschokossi. In the Cameroons, according to the official British report, a tract of "no-man's land " had been left on the frontier between the two spheres of influence, and this [154] had become a refuge for criminal elements. The final delimitation has now done away with this evil, but nothing whatever has been heard of any action being taken by the mandatories to counteract the disastrous effects of the arbitrary determination of the frontiers. The position created in the interior of German East Africa is much worse. Here the sultanates of Ruanda and Urundi were divided from the great mass of the German colony, which fell to the British share, and they were declared to be Belgian mandatory territory. Out of regard for the British lines of communication, however, an artificial frontier had been created, cutting off a large tract of the sultanate of Ruanda. King Msinga and his Watussi were seriously injured by this manoeuvre, their economic existence being actually jeopardized. The matter was brought to the notice of the League of Nations, upon which the British Government agreed to a revision of the frontier line, and thus the sultanate of Ruanda recovered the strip of territory which had been torn from it. But the fact remains that the sultanates of Ruanda and Urundi have been forcibly torn from German East Africa and incorporated in the Belgian Congo. This is a great economic disadvantage for the inhabitants of these two countries, since all their natural connexions are in the territory now under British rule. The reports which the Mandatory Governments present annually to the Permanent Mandates Commission of the League of Nations in Geneva do not as a rule contain anything unfavourable to mandatory administration. From other communications, however, particularly those which have appeared in trustworthy British newspapers and other publications, it is clear that conditions are by no means so rosy as they have been officially represented to be. Three detailed articles in the "Trade and Engineering Supplement" of The Times, the last in the issue of July 30, 1923, deal with the British mandated territory of German East Africa. In these articles the territory in question is referred to as a "bureaucrats' paradise." It appears that the administration employs far more officials than the German pre-war [155] administration, and that the official corps can only be described as a tax-collecting organization; yet, notwithstanding that the heavy taxation imposed on the natives compels them to sell their cattle in order to meet their dues, so that they have sunk into a state of acute poverty, the administration cannot make both ends meet without considerable contributions from the British taxpayers at home. The condition of the colony in general has been described as deplorable. That these opinions are shared by the British living in the colony is plain from extracts from the local Press.11 Other extracts show that in April, 1923, in consequence of the exorbitant taxation, all the Arab and Indian traders had closed their shops, thereby causing serious difficulty in supplying the natives with provisions. Further, the Government procedure had called forth unanimous protest both from Europeans and coloured inhabitants.12 It is stated that since the expulsion of the Germans the plantations of rubber, sisal hemp, etc., which had been brought to a high state of cultivation by the German planters, have for the greater part reverted to wilderness; the natives have less opportunity of earning money; and the pressure of taxation has increased. On the latter point I quote from the Tanganyika correspondent of The Times:

"The present scale of native taxation is a considerable hardship, at a time when the natives have little or no means of earning anything. It is surely wrong that natives should have to sell their cattle at a time when there is no demand for the purpose of raising the money necessary to satisfy the hut tax."13 With regard to the fight against disease, hygienic measures generally for the natives, and school instruction, the British Mandate Government, as may be seen from the details given in the official British annual reports on these matters, has not been able to reach anything like the standard achieved under the former German administration. In the Cameroons and Togoland no less the expulsion of [156] the German planters and traders has similarly led to serious economic results, both in British and French mandated territory. Many of the plantations have been thrown out of cultivation. In the French Cameroons no attempt is made to keep them up, and they are necessarily falling into ruin. In consequence of the reduced possibilities of earning a livelihood, the natives are much worse off than formerly. The entire stoppage of the German hospital service for the prevention and cure of epidemics, which was organized on a most lavish scale, is severely felt by the natives, particularly the lack of measures against Sleeping Sickness. The French have nothing similar with which to replace these German relief organizations, as may be seen from their own official annual reports. One of their chief troubles is the lack of trained doctors and assistants, of whom the German administration had always as many as it needed. In French Togoland confusion and disorder have reigned under Mandate government from the first. Early in 1921 two English travellers, Marjorie and Alan Lethbridge, writing in the Daily Telegraph of their experiences in West Africa, referred unfavourably to the French occupation of the country. The French, they said, had no right to the country, and the subjected tribes would rather be under German rule as before than be forced to serve the French, whom they neither liked nor understood. Mention must also be made of the scandalous frauds by a Commissioner and other high officials in connexion with the confiscated German plantations. In the course of the investigations one of the officials implicated committed suicide and Commissioner Woelfell was recalled. According to the Dépêche Coloniale et Maritime of May 12, 1923, this man left the colony in a state of absolute disorder. A newspaper circulating in the neighbouring British Gold Coast Colony writes as follows respecting the condition of the natives in French Togoland:

"In every household, in the streets, you hear people murmuring and complaining of the exorbitant charges of the customs, licences, and taxes of various kinds levied by the French."14 A Togoland negro expresses [157] himself still more drastically in a letter:

"The present Government is a misfortune for Togoland. They are like wolves. Everything is taxed three times over. Matters grow worse from day to day." Another disadvantage to the natives in the territory under French administration, which includes the greater part of the two German West African colonies, is that owing to the militarization of the colony, now introduced, they are liable to be used for military service outside their homeland. With regard to the South Sea colonies, I will only refer to Samoa and German New Guinea. Samoa, the "pearl of the South Seas," must be included in order to tell of the tragic fate that has overtaken its inhabitants, one of the most amiable populations on earth. This tragedy is a direct result of the incapable Mandate administration of New Zealand. The Chicago Daily Tribune of September 22, 1920, drew attention to the signs of retrogression and decay which had already overspread the colony since the Government of New Zealand took over the administration: though taxation had become intolerable, everything was falling into ruin; large plantations had been allowed to become desert, and the pineapple industry had been destroyed; while the treatment of the expelled Germans was described as barbarous. The Brisbane Daily Mail, in February, 1921, likewise condemned the harrying out of the island of the German planters and their replacement by inexperienced men as a fatal blunder, and reported that the inhabitants were burdened by taxation, the only people who benefited being a crowd of officials of all kinds. The result was general discontent on the part of the Europeans and natives equally. In an article entitled "Who said Humanity?" the former American Consul at Apia has also testified to the cruel eviction of the Germans, whom he knew as industrious and efficient men, and told how the grateful natives assembled to witness their departure. Further, during the war the dreaded Spanish influenza was by some means introduced into the colony, and in consequence of the incapacity of the New Zealand authorities, it spread to such an extent that one-fourth of the population [158] are reported to have died of it. Here the Mandate administration has fallen short in nearly every direction, so that the old inhabitants, the British and other white settlers and the Samoans alike, have protested in equally strong terms. Reference to German New Guinea is the more pertinent since here the contrast between appearances and facts is particularly crass. The make-believe of a successful Mandate administration assiduously engaged in developing the country, as would appear from reports sent to the League of Nations, and from other official publications, is contradicted by the dismal reality of decay, disaster, and false methods of government, of which abundant evidence comes from undeniably reliable sources. By the Treaty of Versailles the Allied Powers took the right, in defiance of international law, to appropriate the private property of Germans in all the colonies, and the Australian Government enforced this "right" in German New Guinea with great cruelty. From the time the colony was occupied by Australian troops until two years after the Armistice the German planters and merchants were allowed, and even encouraged, to carry on their plantation and commercial enterprises as usual. This they did with great zeal, seeking relief in that trying time of strain and suspense by redoubled energy and concentration upon their work; new plantations were laid down, and other developments and improvements carried out. Then just before Christmas of 1920 three vessels laden with young returned soldiers were landed on the island, and without notice or respite of any kind the Germans were ejected from their properties and turned out of their homes, and the totally inexperienced new-comers were at once put in charge as factors. Most of the evicted Germans were deported, being chiefly shipped to Germany at their own expense, even though this was covered in the case of employees by appropriating their hard-won savings. In its issue of July 22, 1921, Stead's Review, published in Australia, described the "refined cruelty" with which the Germans were robbed of their property and driven out of the country. Writing of this amazing act of folly, a Melbourne [159] correspondent of the Manchester Guardian wrote of the new managers (August 2, 1921):

"They knew nothing about coconut growing, and less about the handling of natives. The inevitable has happened. The best of the native workers, who had been long on these plantations, refused to renew their contracts, preferring to go back to their own villages and await developments. The German 'boss' they had known for years - they had no confidence whatever in the young Australian 'boss' who had superseded him. Thus it has come about that the plantations are rapidly deteriorating, and at the same time the Expropriation Board is confronted with an acute shortage of labour. A contributor to the Westminster Gazette (October 20, 1921) wrote strongly to the same effect. It was no better with the officials sent to administer the colony. So inexperienced were they that the German planters had to be asked for suggestions as to how the work should be carried on. In an article contributed from Raboul to the Empire Number of The Times of October, 1924, a correspondent states that the Australian Government had so far failed to fill the gap caused by the replacement of the Germans. He writes:

"But the big problem still remains. Australia has to render a strict account of her stewardship in New Guinea. Her well-meant efforts to throw out the German capitalists have scarcely resulted in the development of the country; her success in handling a black race that is a shade in advance of her own primitive aborigines is still to be proved." That is putting the case mildly from the standpoint of a friend; for the hard facts are deplorable in the extreme. [160] It will suffice to cite the report of Mr. Ellis, a special correspondent sent to German New Guinea in 1923 on behalf of the Sydney Daily Telegraph. He supported his statements by numerous photographs of the plantations and cultivated territories, which were found to be neglected to an incredible degree. Everything which German industry had accomplished had been lost to civilization. Some of the unhappy German planters, whose land had been illegally taken from them by a breach of faith, were still in the colony, living in hopes that their eviction and the confiscation of their property, against which they appealed long ago, might yet be revoked. Meanwhile, they were compelled to look helplessly on while the land which during years and even decades of patient labour they had wrung from the tropical bush, suffering untold hardships and often falling a prey to disease, was being allowed to fall into decay as a result of unspeakable maladministration. The official treatment of the natives is no better. According to the same correspondent the administration of justice is attended with various abuses, so that, as he says, "no words could be too strong to condemn the system as it stands." In that year the situation was so desperate that an expert British colonial official had to be appointed to investigate it, and in July, 1924, the Australian Government promised a Royal Commission on the subject if the report of the investigation made it advisable. In this connexion The Times of July 3, 1925, reporting on the action of the Mandates Commission of the League of Nations, stated in regard to New Guinea:

"A special report has been drawn up over and above the official annual survey. The local authorities, being fully aware of their own embarrassments, themselves invited an outside opinion, and a British imperial administrator of standing and experience was sent, who has had some frank criticisms to make." Only lack of space prevents me from enlarging further upon the results of the Mandate administration in the German colonies. The reader, however, may be referred to my book, published in 1922, The German Colonies under the Mandates,15 in which much more is said on the subject in the light of the [161] material then to hand. I wrote therein as follows upon the result of the investigations which yielded this material:

"This result is absolutely annihilating for the majority of the colonies and the Mandatories. The Mandates have proved to be a great failure. Present conditions in these countries are in every respect infinitely worse than they were when the Germans were in possession. The German colonies are now in decay, economically and culturally. The most evil consequences for the natives arise from the collapse of the Mandatories in the matter of combating epidemics and in general health measures. The natives are absolutely dissatisfied with Mandate government." This verdict was quite justified at that time. It cannot be maintained equally to-day for all those territories, because in the meantime some economic progress has been made. But even in those mandated territories where the greatest development has taken place it is only now that the pre-war conditions have been even approximately reached in economic affairs, while the humanitarian institutions - especially those relating to sanitation and education - are still far behind our standard.

2As reported in The Times at the time. ...back... 3Cf. Official Report of Parliamentary Debates, p. 509. ...back... 4Cf. Report on the British Sphere of the Cameroons, Parliamentary Publications, May, 1922, p. 62. ...back... 5Ibid., p. 68. ...back... 6Landeszeitung for September 18, 1920. ...back... 7Report of the proceedings in the Westminster Gazette, August 16, 1920. ...back... 8Rapport au ministre des Colonies sur l'administration... du Cameroun de la Conquête au 1 juillet, 1921, p. 434. ...back... 9Rapport, 1921, p. 24. ...back... 10L'Intransigéant, as quoted in the Hamburgische Korrespondenten, August 18, 1923. ...back... 11Cf. Dar-es-Salam Times, August 25, 1923. ...back... 12Ibid., April 21 and May 5,1923, and African World, May 26, 1923. ...back... 13The Times, May 24, 1923. ...back... 14Gold Coast Independent, April 24, 1923, cited by the African World of May 19, 1923. ...back... 15Published by Quelle and Meyer, of Leipzig. ...back...

|